We had a wonderful time in southern Brittany (Loire Atlantique region) in July and August. Of course, it was high season and the harbours and anchorages were therefore quite crowded. But that didn’t detract from the beauty of the area and the laid-back attitude of the people there. The French way of life is really very pleasant. Enjoyment is celebrated in a relaxed manner and almost everything can be handled with patience and humour. The openness and friendliness of the French in the marinas and elsewhere is great. However, if you are not reasonably fluent in French, it is better to switch to English, as the French seem to prefer this and it is usually sufficient for smooth communication and small talk.

Our highlights were Pornichet, Piriac sur Mer and the beautiful anchorages around Ile d’Houat and Hoedic. Thanks to the predominantly good weather, the experience was almost like what you imagine the Caribbean to be like.

It was with a heavy heart that I made the decision back in the summer not to take the ship across the Bay of Biscay and on to Spain and Portugal to spend the winter there, but to bring it back to the Baltic Sea. It just turns out that for family reasons there are only a few weeks a year to be on the boat. Getting on a plane every time to sail in the most beautiful areas of Europe cannot compensate for the long weeks in which the ship is moored in expensive harbours and cannot be reached at all. It’s better to have the boat close by and maximise your time budget in the summer to make the longest possible trips to beautiful and accessible areas.

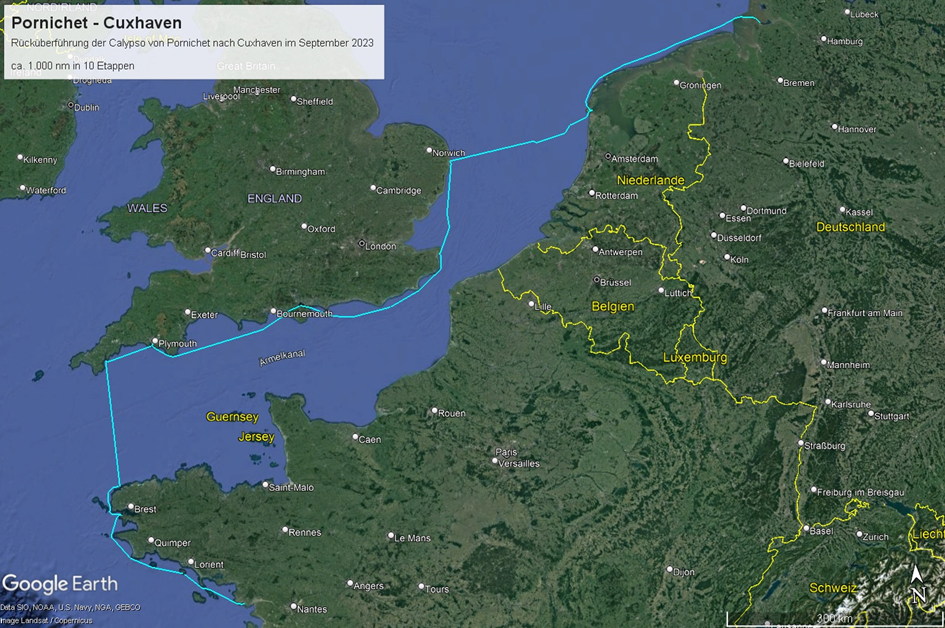

So the plan is to bring the boat back to the Baltic Sea from 8 September. I have to return home for a week on 28 September. Let’s see how far I get by then. I have another week from 5 October to complete the transfer.

I plan to sail back via the southern English coast this time for several reasons:

The predominantly tide-independent harbours on the southern English coast are located at relatively comfortable distances of around 60 nm and are usually well protected from westerly winds, as they are either in river estuaries or on the east side of huks. There are no real races here like on the French side. I also really want to get to know the south English coast, who knows if I’ll ever come back here. To do this, I have to allow for about 150 nm more distance.

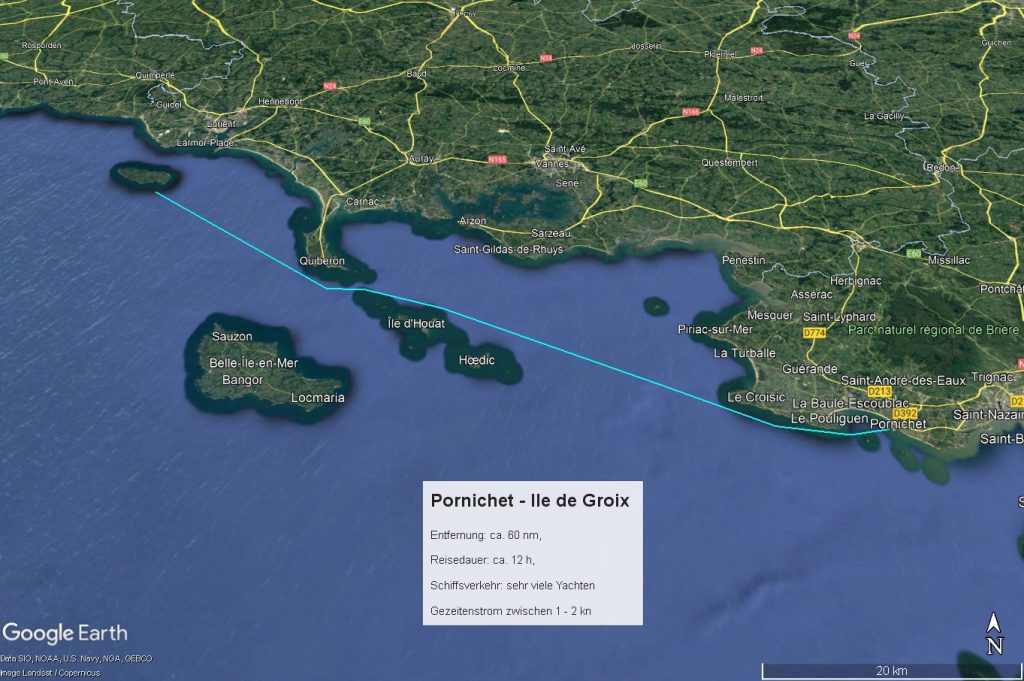

Etappe 1: Pornichet – Ile de Groix, ca. 60 nm, ca. 12 h

I arrive late on Friday night and spend Saturday stocking up and preparing the boat for the trip. The “highlight” is the obligatory dive to remove the worst of the fouling near the waterline and on the saildrive. Once I’m around and just want to brush the log a little free, I notice that there’s a veritable cluster of mussels and algae hanging under the keel. I can’t believe my eyes, dive down and sure enough: a huge lump has grown under the keel sole, hanging under the sole like a giant keel bomb. I have to dive down at least 20 times to completely remove the lump with a spatula. It’s exhausting. Luckily the weather here is still summery, it’s still very warm at night and there are mosquitoes and weather light.

It’s completely calm on Sunday morning and I realise that I’ll have to motor for at least the first few hours, if not the whole day. I prepare the boat for casting off, a friendly neighbour comes to help me and at around 08:00 I leave the still sleepy harbour and head out into the Atlantic. I take a look around and feel a certain sadness at having to leave this beautiful harbour and the memories of a wonderful summer here behind me for good. As I pass Le Croisic, I see that a huge thunderstorm is coming down behind me over Pornichet, which now spares me, but unfortunately without any significant wind.

The sky clears around midday, again without any wind to speak of. I first motor past the islands of Hoedic and Houat, which appear to still be summer paradises, and then reach the southern tip of Quiberon, where there is finally some wind. From here I can continue sailing at 3-4 knots to Ile de Groix.

As the night is expected to be calm, I decide to anchor in the outer area of Locmaria Bay.

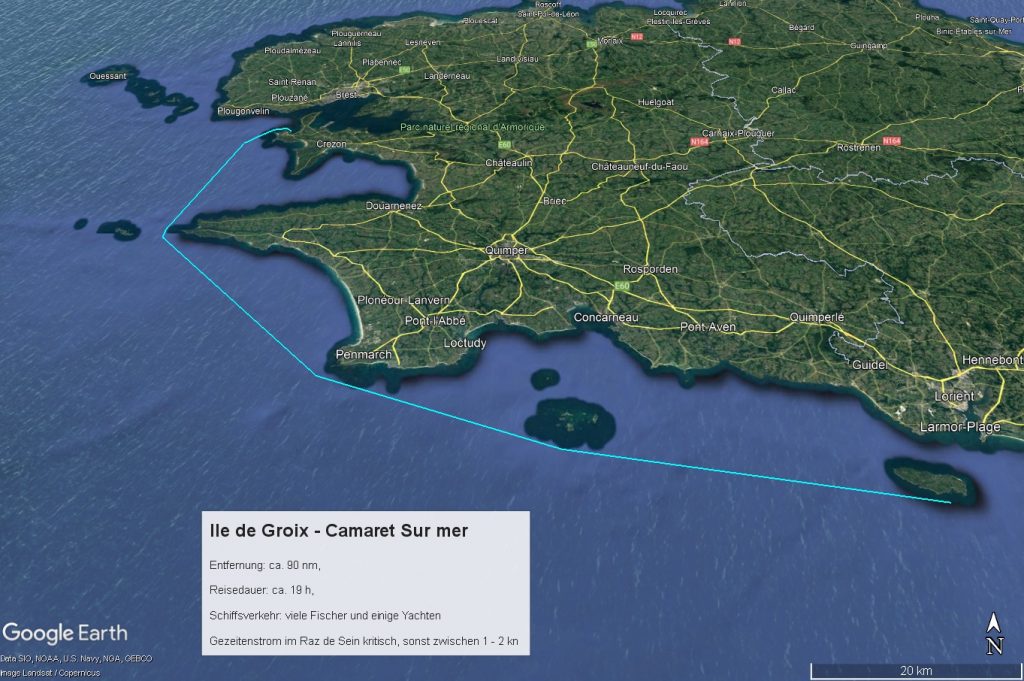

Etappe 2: Ile de Groix – Camaret sur Mer, ca. 90 nm, ca. 19 h

The next morning I set off early at 6am because I want to pass the Raz de Sein heading north at around 10pm. As I have very little knowledge of the area, I strictly adhere to the recommended passage times in the Reeds. A pack of dolphins accompanies me along the west coast of the Ile de Groix. Unfortunately, the wind is a long time coming, so I struggle northwards at a tiring 4.5 – 5 knots. Around midday, I pass the Iles de Glenan, which I would have liked to take a closer look at, but my time budget doesn’t allow it. As a consolation, some wind comes up so that I can sail at 4-5 knots and do without the engine.

At Audierne the wind dies down again and I have to continue under engine.

I reach Point du Raz at around 10 p.m. and the passage of the Raz de Sein is unspectacular, although visibility is poor and the fog is thick in places. Around midnight it clears up and I am accompanied by a fantastic starry sky and sea lights. The large beacons are all very clearly visible.

Coming from the SW, Camaret Sur Mer lies behind a Huk and the lights of the harbour are only visible shortly before. Despite the electronic chart, it always feels a bit strange at night.

Around 3 a.m. I moor at the floating dock in Port Vauban and fall into my bunk.

This was probably the slowest leg of the entire trip: just under 90 nm in just under 19 hours at an average speed of 4.5 knots, mostly under engine power. The passage of the Raz de Sein is a milestone for me because I no longer have to fear the prevailing westerly winds, but can make the most of them. From now on, I want to take my time and only sail with the right winds.

The next morning I see that the harbour is at most 50% occupied. The harbour master comes by with the RIB and asks me to come to the office to pay. The wind is forecast to be light, so I enjoy the day in the harbour, stock up on supplies and stroll through the beautiful but also very touristy town.

Right by the harbour there is a beautiful little seafaring church and right next to it are several large wrecks of fishing trawlers that have been rusting away here for decades. Several yachts are anchored in the bay in front of the harbour. A light south-westerly wind is blowing, the sun is shining, an almost Caribbean flair.

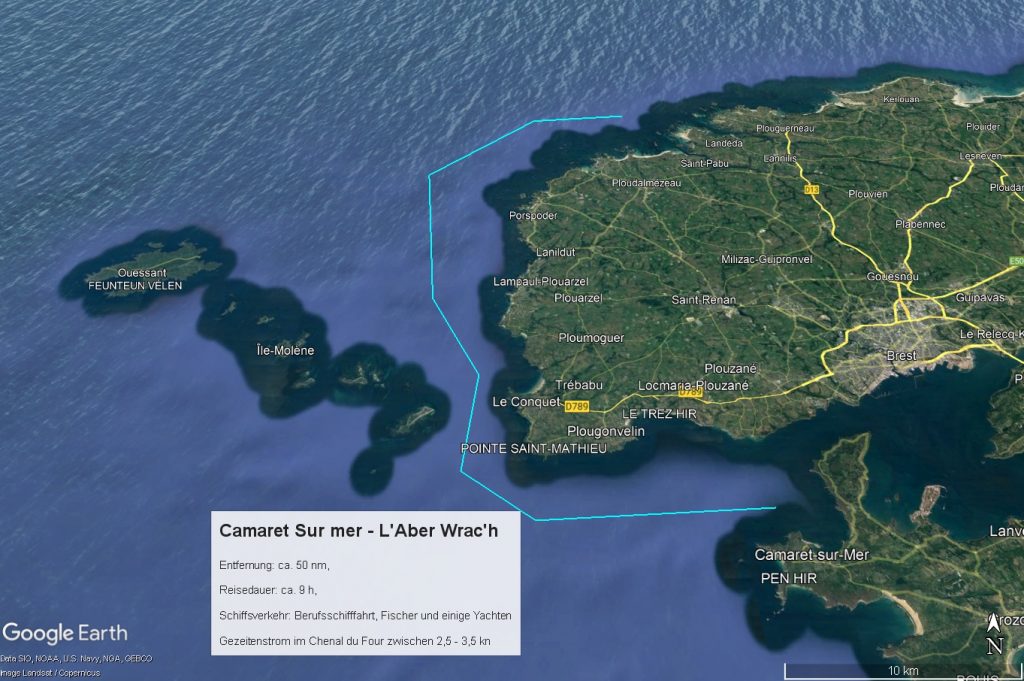

Etappe 3: Camaret sur Mer – L’Aber Wrac’h, ca. 50 nm, ca. 9 h

The next morning I store up on diesel and set sail immediately after leaving the harbour, heading upwind towards Chenal du Four. I reach Pointe Saint-Mathieu just as the tidal current capsizes and start heading north. A Swedish 15 metre yacht is slightly ahead of me and we start a thrilling match race. The apparent wind picks up a little due to the “wind against current” situation and I put a reef in the main. It’s fantastic sailing and slowly but surely I work my way past the Swedes. Not because I’m faster, but because my boat is gaining more height.

At around 3 pm I go to a mooring off L’Aber Wrac’h and am immediately welcomed by the friendly harbour master, who instantly collects a hefty fee and offers to take me ashore in his RIB.

Later, I am visited by my neighbours, who sail under the British flag but are native German speakers. They live on the English south coast and give me lots of good tips and advice for my further journey along the English south coast.

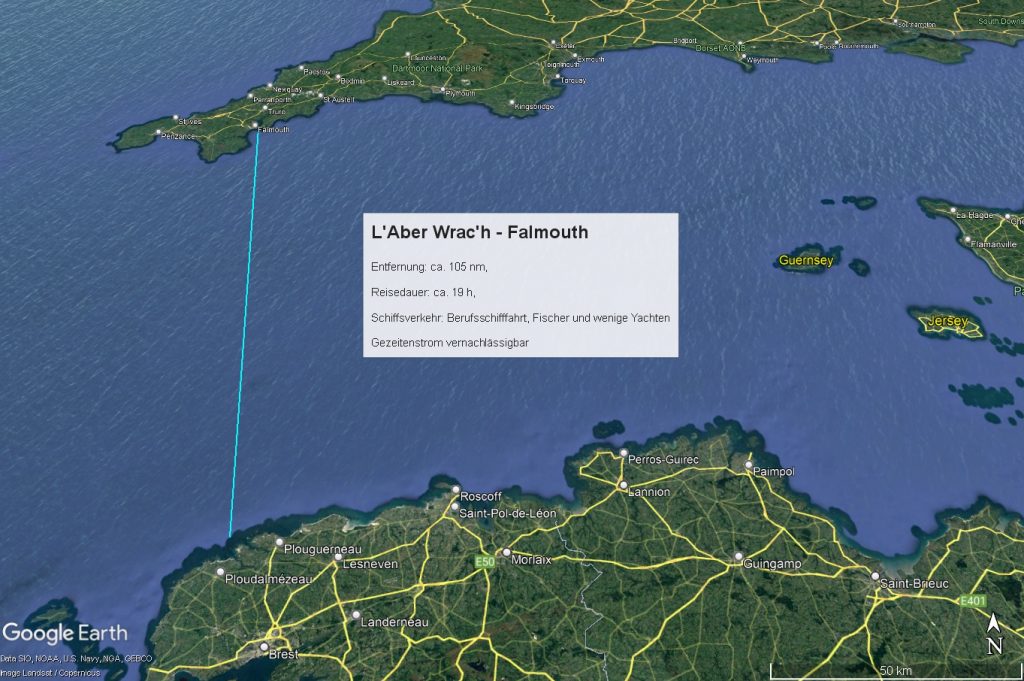

Etappe 4: L’Aber Wrac’h – Falmouth, ca. 105 nm, ca. 19 h

The day starts with complete calm and patches of fog. I use the morning to check the engine, the alternator and the B2B charger.

A light south-westerly wind is forecast for the afternoon and night. That’s why I want to set off towards Falmouth at around 15:00 as the tide is running out and plan to sail through the night. Brittany bids me farewell with a real summer’s day.

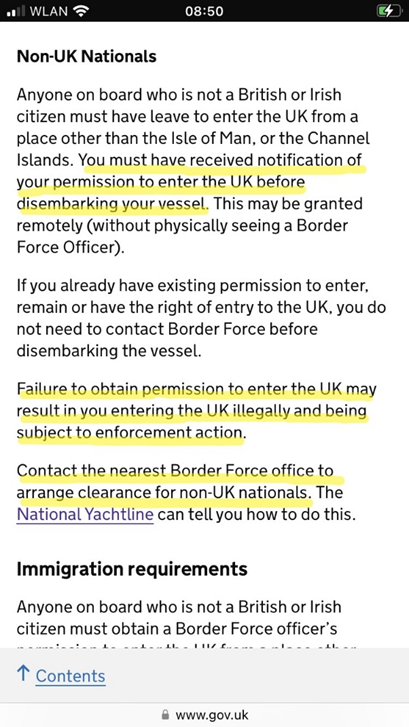

The entry regulations to the UK for non-British people on pleasure crafts are somewhat inconvenient: Passport and registration (pleasure craft report) via app or online form with the customs authorities (HMRC) are mandatory. When entering the 12-mile zone, the yellow flag “Q” must be displayed. The vessel may only be left after entry if express authorisation has been obtained from the border authority. Failure to do so may result in a fine. So far, so clear.

Submitting the “pleasure craft report” via the app works without any problems and the confirmation of receipt is also there immediately. I’m curious to see whether the actual entry process will go just as smoothly afterwards.

After casting off at around 3 p.m. I chug NW for the first two hours until, as predicted, a light SW wind slowly sets in, which increases to 10 – 12 knots in the evening and lasts all night.

The commercial shipping traffic concentrates on the shortest route between the traffic separation schemes and is quickly passed. Only a few fishing boats are annoying because they frequently and unexpectedly change course and demand attention.

Apart from that, it’s wonderful sailing through the moonless night with the main and jib. The starry sky is indescribable and the glow of the sea shimmers from below, it’s a sight to behold. The only scary thing is the radar echoes not too far away, about halfway along the route, which I can’t assign to either position lights or AIS signals. As some of them are moving fast, I suspect that they are RIBs, probably (hopefully) British navy or customs. Or are they smugglers? On entering the 12-mile zone at dawn, I report to Falmouth Coastguard via VHF. I arrive in Falmouth at around 09:00 in the morning.

It’s really amazing: there are hundreds of boats moored at the moorings or anchored in the river and in comparison there are very few places in the relatively small marinas. I would estimate the ratio at 10:1. Due to the easterly wind forecast for the next few days, I will have to spend two days here and therefore decide in favour of Pendennis Marina because it is close to the town and promises sufficient draught. I’m lucky and get a place over the radio. The marinas are full here and pure luxury, as I realise later when I pay. As a rule of thumb: in Germany you pay between €20 and €30 per night for a 12-metre boat in a well-equipped marina, in western France €30 to €40 and in Cornwall £40 to £50.

I get myself some hours of sleep and then go to the Chain Locker for a portion of fish and chips, which is a blatant violation of British immigration regulations, but is now really urgent. The Chain Locker is a nice restaurant with a beautiful terrace and harbour view (and above all a delicious pale ale), which friendly sailors in L’Aber Wrac’h had recommended to me.

I then try to find out where and how I can get an entry permit from the border authorities. There are no customs or border guards to be seen for miles around. The app lists a few phone numbers. When I finally reach someone after many attempts, the person explains very kindly that his authority is not responsible and that he doesn’t know why his phone number is in the app. However, he is at least able to give me the number of the relevant border authority in Plymouth. I don’t reach someone there until the next day, who at least declares himself responsible and even finds my entry application submitted via the app in his system. When I ask whether this call means I now have official authorisation to enter the country and can leave the ship, he says yes, in principle I do, as long as he doesn’t call me back in the next few minutes. Quite a cheeky procedure with an astonishing degree of commitment. But well, we are in the land of Monty Python …

Just opposite is the National Maritime Museum: here you can see the dinghy and other parts of the shipwreck of the Robertson family, who lost their ship in the Pacific in 1971 due to an orca attack (!) and survived 37 days with 3 adults and 3 children in a life raft and a dinghy until they were rescued by Japanese fishermen: truly an incredible story Shipwrecked: nightmare in the Pacific | Family | The Guardian. Otherwise, many individual pieces are shown and piracy in the 16th – 18th centuries is pretty much the centre of attention, but rather luridly presented and addressed to children and young people.

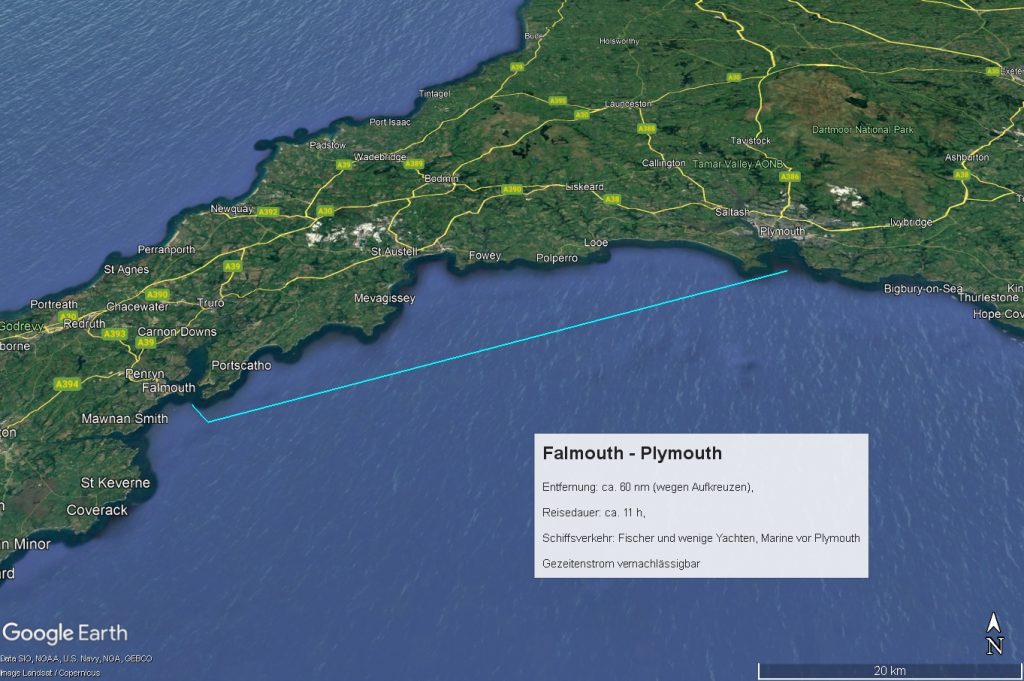

Falmouth – Plymouth, ca. 60 nm, ca. 11 h

The second night in Falmouth is very restless, because around 3 o’clock in the morning the strongly increasing easterly wind begins to send an unpleasant swell to the jetty, which is also chaotically reflected and amplified by the quay walls.

According to the weather forecast, the wind should become more southerly with 13 knots in the morning at around 11.00 a.m. and then from around 1.00 p.m. almost southerly and down to 10 knots. In the evening it should turn SW and weaken further. The tidal stream capsizes at the Start Point lighthouse shortly after 24:00, turning from east to west. My plan is to round the cape at Start Point before midnight (distance from Falmouth approx. 60 nm) and then anchor for a few hours in the lee behind the Start Point huk and sail on towards 06:00 in the morning to then round Portland Bill (distance approx. 40 nm) before 12:00 with the current turning north-east and head for Weymouth.

However, things turn out differently than planned. As soon as we cast off at around 10.00 a.m., it was clear that, contrary to the forecast, the wind was already coming from the east at 5 – 6 Beaufort in the sheltered area of the Fal River. Double reefed main and only half furled jib are already more than enough sail area in the coastal area to chase the ship out to sea at 7 knots. So 6 – 7 Beaufort at sea. Really tough sailing and, at 150 degrees initially, not the course I actually wanted to take. Plus a strong sea and heavy squalls. Should I turn back? But the forecast for the next few days is for really heavy weather from the west. So I carry on.

Under these conditions, I can only tack slowly to the east in the hope that the wind – as forecast – will drop and turn to the south. After 4 tedious hours of tacking, during which I had not made up more than 12 nm to the east, the wind finally began to moderate and become more southerly. I was able to furl the jib completely and lay it at about 70 and then 90 degrees, and now I was travelling quickly eastwards. When unfurling the jib, I notice that the luff is sagging slightly below the guide rail, but I don’t pay any attention to it for the time being.

After 2 hours of brisk sailing to the east, the wind first dies down so that I can take the reef out of the main and then drops to 8 knots, so that the wind is no longer sufficient to get the boat through the swell at more than 3 – 4 knots. So we add the engine. At around 18:00 the wind shifts back to ESE, so I can only set course for Plymouth. Of course, I can forget my schedule of rounding the cape at Start Point around midnight.

So change of plan: call at Plymouth and set off again very early the following morning to round Start Point around midday and then at least go as far as Dartmouth or Brixton. Weymouth cannot be reached tomorrow because strong winds are forecast from the afternoon of the following day and storms for the following days.

In the Sound of Plymouth, the jib suddenly jams as I furl. With a bit of jerking she gets going again, but I realise that something is wrong. Moorings and anchorages outside are all too rough for me in the SE wind, so I head for the nearest Mill Bay Marina first.

At the mooring, I unroll the jib again to find out where it is stuck and whether there is a problem. And indeed: it can only be unfurled and furled again with a lot of jerking. It also can’t be lowered, something is jammed at the top of the mast. Definitely not a situation I would like to have when travelling in unfavourable circumstances.

The next morning I see that the drop guide eye has come off and the resulting slack in the drop has rotated around the guide rail. I realise that I need to have this done. I do some research and find “Hemisphere Rigging Services”, a rigging service that seems promising. I call them, describe my problem and they promise to call me back. And indeed, after half an hour I get an appointment to come to Plymouth Haven Marina on the same day to check the damage and repair it if necessary.

And right on time, a team of two very friendly and young riggers arrive, one of whom, after a brief clarification, boards the mast and installs a new halyard lead eye while his colleague secures him with the halyard on the winch. It really is unbelievable: the colleague actually boards the mast with his hands and feet and under his own steam. Of course, he pulls himself up in a bag with his tools. I’ve only ever seen this kind of hands-free hoisting once before in Brittany with a young training crew, but they did it more as a joke or sporting show-off. Here it’s professional work. Unthinkable in Germany. It all takes less than an hour. The bill is £105, I almost can’t believe it and can hardly believe my luck.

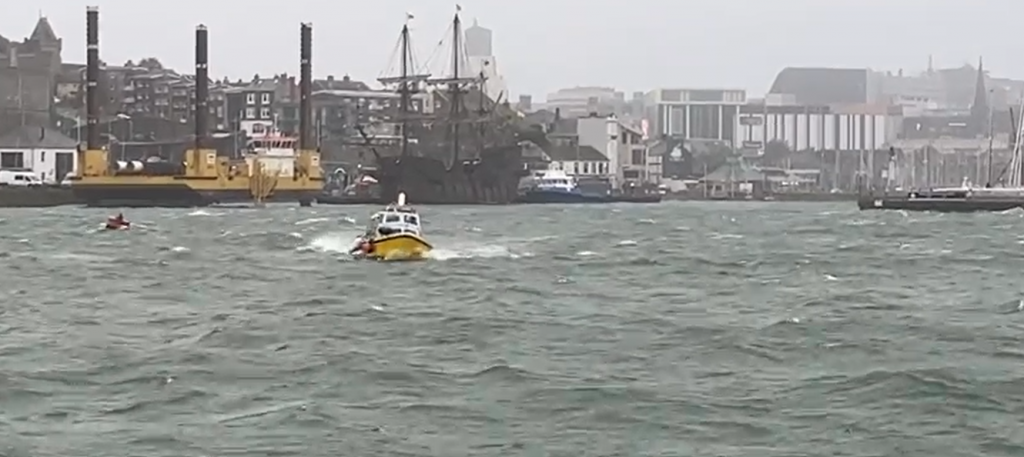

The wind picks up more and more as the day progresses. I spend another 2 days in Plymouth while a storm blows through with up to 9 Beaufort. Time passes quickly, there is plenty to see in the small town, which is well worth a visit, including a gin distillery and the Mayflower Museum. There is also a faithful and sailable replica of a Spanish galleon at the Barbican Pier, which can also be visited. Only the short crossing from Mount Batten to Plymouth harbour takes a little getting used to for me, the locals don’t bat an eyelid even in 9 Beaufort winds.

Although there is no direct swell in the harbour, there is an underlying strong movement in the water that makes the ship work quite hard in the lines, which doesn’t really make the stay comfortable. I’m looking forward to sailing on tomorrow.

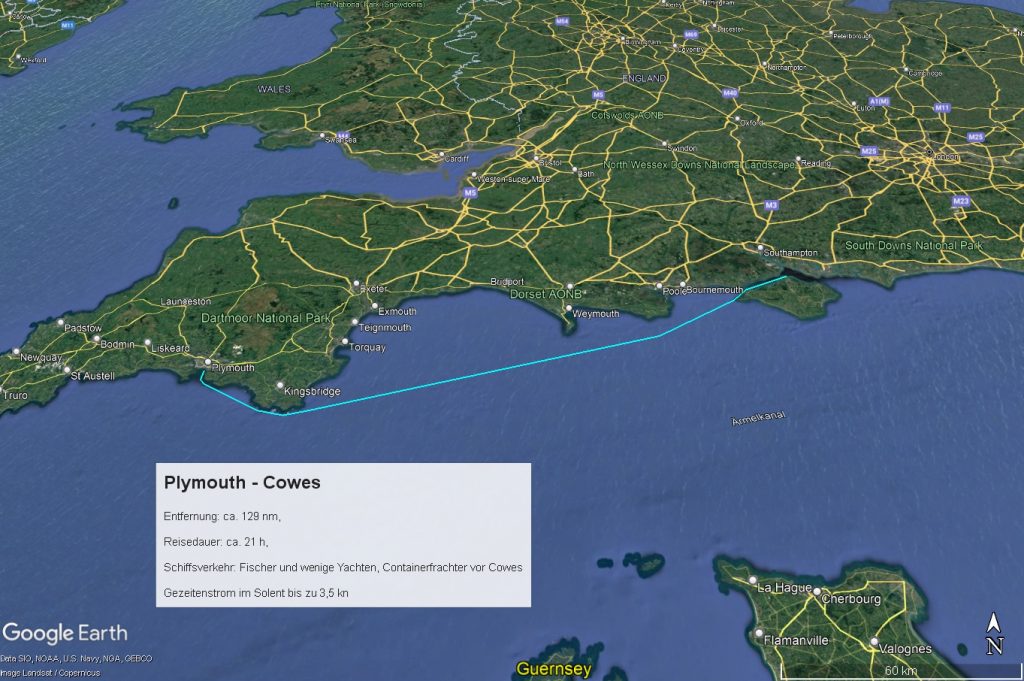

Plymouth – Cowes, ca. 129 nm, ca. 21 h

I leave Mount Batten Marina early in the morning when it is completely calm. But just beyond the huge breakwater that protects Plymouth Sound, the wind picks up and comes from starboard at 4 – 5 Beaufort. That’s good, because there’s still a lot of old swell from the storm the days before, so wind pressure in the sails helps. We make good progress and by lunchtime I’m already passing the entrance to Salcombe against a picturesque landscape backdrop with the current flowing along and at times over 8 knots over ground. I regret that I don’t have time to cross the barre into the river and spend some time there. But I have to make good time now because I have to be back home on 28 September and want to get the boat as far as possible by then.

Now Lyme Bay lies ahead of me and the current will continue to run with me until around 3 p.m. after which it will run towards me until around 10 p.m. I therefore keep a distance of about 10 nm from Portland Bill to avoid the up to 3.5 kn strong counter current. In the afternoon I see an almost circular, white foaming area ahead in the water, over which seagulls are circling excitedly and swooping down again and again. As I get closer, I also see that quite large fish keep half jumping out of the water, but nowhere near as high and elegant as dolphins: I assume that tuna are chasing a school of fish and the seagulls are joining in. A beautiful spectacle. Around 8 p.m. I pass Portland Bill, around 1 a.m. Anvil Point and around 3 p.m. I pass the Needles and enter the Solent. Unfortunately, it’s so pitch dark that I can’t even make out the Needles, which is a shame. Shortly before entering Cowes, a huge container freighter comes towards me and turns into the Southampton Waters in front of me. I moor in Cowes Yacht Haven at around 05:30 p.m.

I enjoy the day in the British sailing Mecca, everything here is geared towards sailing regattas and the most impressive yachts can be seen. The marina prices are, of course, dizzying. There are lots of interesting shops and restaurants, some with live music in the evenings, and it’s fun to stroll around here. There are also several monuments and plaques commemorating the heavy air raids by the Germans during the Second World War. It must have been pretty intense in this area at times.

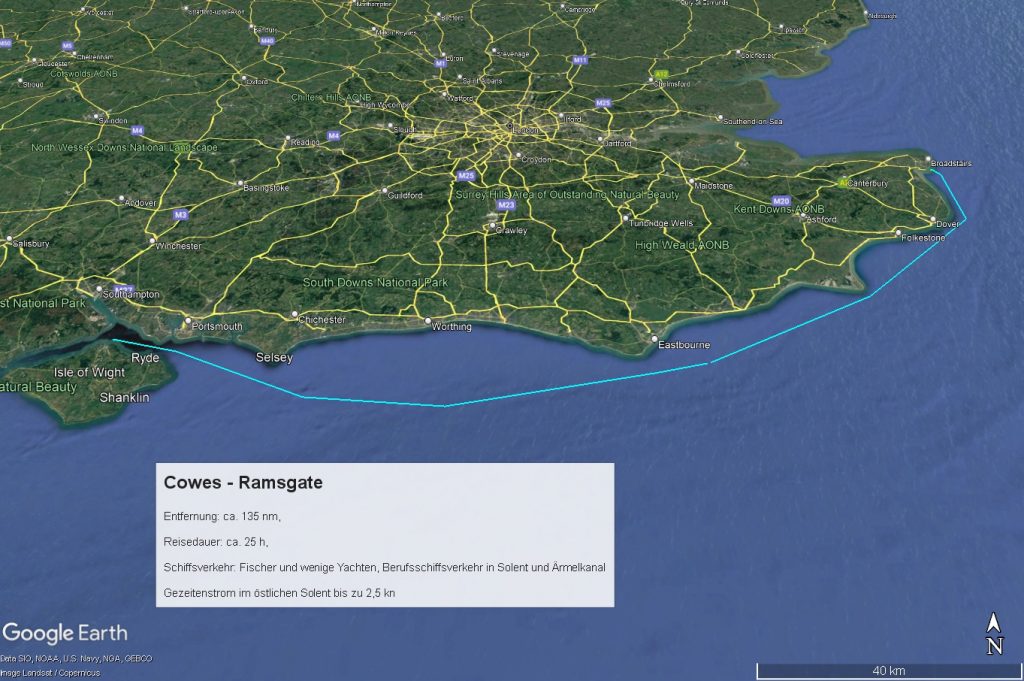

Cowes – Ramsgate, ca. 135 nm, ca. 25 h

The following morning starts sunny, but with a light wind, so I make slow progress for the first few hours under the main and out of the jib.

At around 11 a.m. I reach the huge former defence structure “No Man’s Land” south-east of Portsmouth, a real monster, 60 m in diameter and 20 m high: No Man’s Land Fort – Wikipedia . Progress continues to be slow and it is not until around 2 p.m. south of “The Looe” that the wind finally picks up and we make headway with a rough wind and 6 – 7 knots.

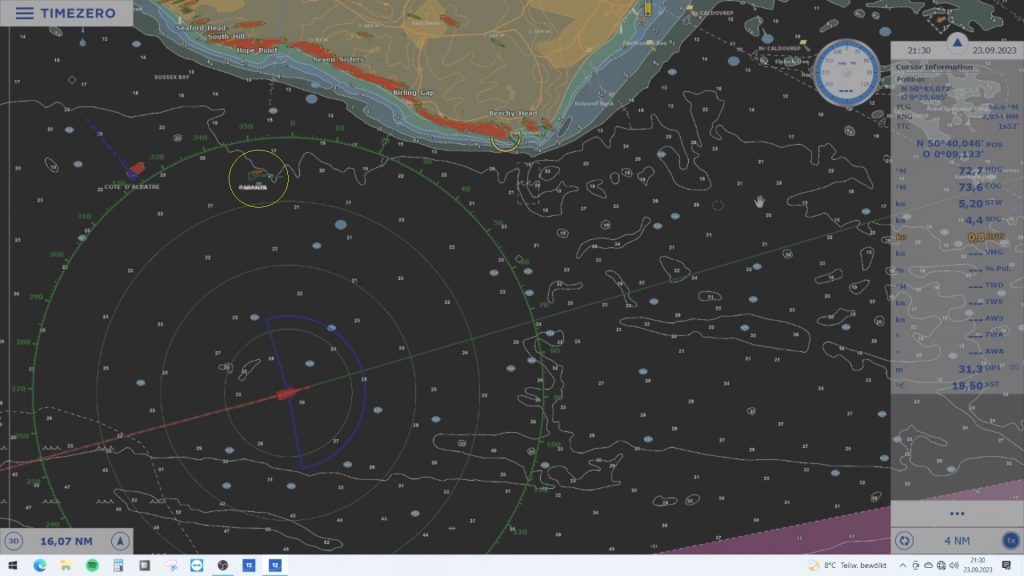

Towards evening I pass a huge wind farm and then head east parallel to the English Channel traffic separation scheme. Around 9:30 p.m. I see a German sailing yacht on the AIS south of Beachy Head, which is running a parallel course a few miles to the north, very close to land. Although I’ve now taken down the jib due to the steadily increasing wind and am only sailing with the main reefed, I can keep up a good pace. After passing Beachy Head, we slowly get closer and later I can also make out their position lights.

The tidal current capsizes at Eastbourne and it gets pretty bumpy. It is now around 0200 in the morning. The other yacht maintains its course while I turn a little further north to stay parallel to the coast and out of the traffic separation scheme. The other yacht gets closer and closer and soon crosses my course at a distance of a few hundred metres and continues at an acute angle towards the traffic separation scheme. I wonder what advantage this is supposed to bring and whether the skipper knows what he is doing or whether he has perhaps even fallen asleep and the autopilot is simply stubbornly continuing to sail the set course.

When the yacht is only a few hundred metres away from the really busy traffic separation scheme, I can no longer stand idly by and radio her several times via DSC. No response, the course continues at an acute angle directly towards a large freighter that is making its way between others. This seems really strange to me now, so I call the Coast Guard and draw their attention to the situation.

The yacht does respond to the call from the Coast Guard on channel 16 and a female voice confirms, slightly stroppy, that they intend to cross the traffic separation scheme at an acute angle towards France. The Coast Guard issues a warning and announces that it will continue to monitor the situation. In retrospect, I’m a little embarrassed to have “told off” the other yacht, but the behaviour was just so unusual that I was worried and didn’t want to stand idly by.

The down wind has now increased to 6 – 7 Beaufort and I’m glad to be travelling with the main reefed. At around 6:30 a.m. I pass Dover with the tidal current still running and it slowly starts to get light. At around 8:30 a.m. I steer into the shallow waters off Ramsgate and head for the harbour. I register via VHF in accordance with the regulations and ask to be allowed to enter the outer harbour under sail so that I don’t have to take down the sails out in the rough sea. I get permission and head for the entrance at 7 knots, having to keep about 30 degrees ahead to avoid making a dog turn. The current shift and the wave in front of the entrance are impressive.

I lower the main in the outer harbour and enter the inner harbour. The entrance allows the swell to run almost unhindered into the harbour: Yachts and jetties dance up and down violently. It’s not easy to moor single-handed in a swell like this. But it goes without a hitch and after registering with the harbour master I can treat myself to a few hours’ sleep. There is another harbour basin that is sheltered behind a lock, but as I want to continue straight away in the morning, I put up with the swell.

In the afternoon, I stroll through the town. The interesting buildings on the cliffs make a beautiful façade on the sea side. There are lots of restaurants and bars, including a kind of spa hotel right on the harbour. However, the town centre behind it looks a little run-down. There are a few nice pubs, but quite a few shops stand empty with their windows boarded up.

The town presents itself as a bit of a seaside resort, the harbour itself no longer seems to be of any great importance, with yachts moored in the two marinas here, and a few fishermen and feeders for the windparks and oil rigs alongside.

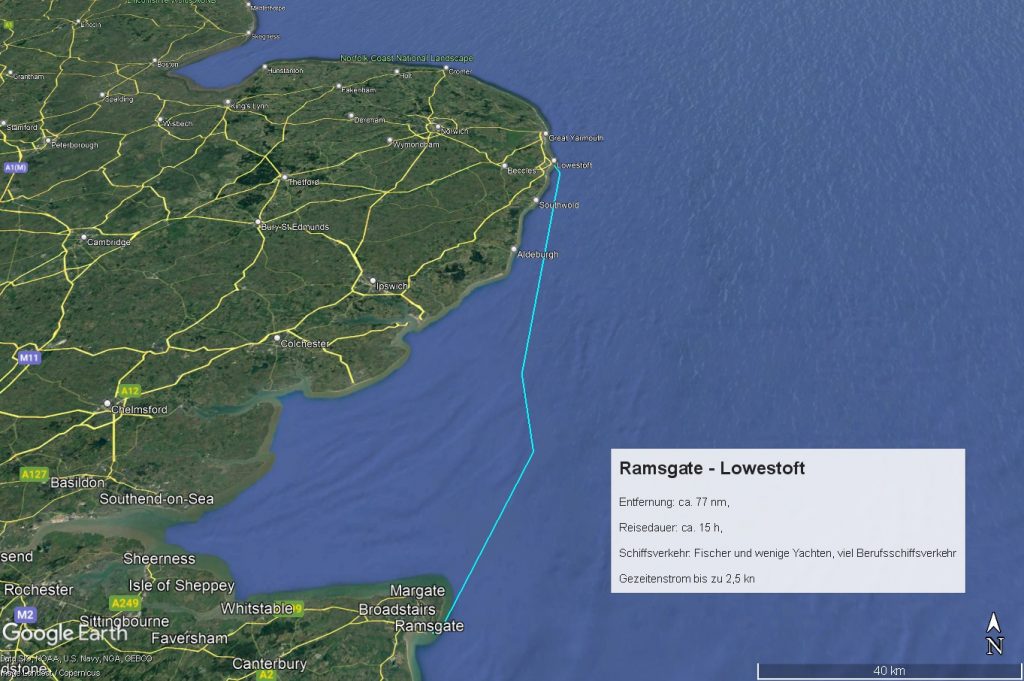

Ramsgate – Lowestoft, ca. 77 nm, ca. 15 h

The original plan was to go from Ramsgate across the North Sea to Scheveningen, a trip of about 120 nm zigzagging through the complicated traffic separation schemes and wind farms of the southern North Sea. The wind is still coming from the south, but has dropped considerably compared to yesterday to 2 – 3 Beaufort. That would mean sailing at just under 5 kn under engine power until the wind picks up again in the coming night. I would probably only arrive in the morning and have to leave the boat in Scheveningen while I have to go back to Berlin for almost a week. Not a great prospect, especially as Scheveningen is one of the most expensive marinas on the Dutch North Sea coast. So I decide to realise the alternative I had already thought of, namely to head north on the English side to Lowestoft and then cross the North Sea the next morning straight to Den Helder and leave the boat there.

I set off from Ramgsate at around 07:00 a.m. and have a travelling tidal current for the next few hours. At around 09:00 a.m. the wind picks up to around 10 knots and I set the main and boom out the jib. However, the wind pressure is weak and criss-crossing swell causes the sails to beat again and again. I finally decide to set the bora, which pulls us wonderfully northwards for the next 5-6 hours.

As dawn breaks, the wind drops and I have to use the engine again for the remaining two hours to Lowestoft. At around 2300 hrs I moor in Lowestoft at the Royal Norfolk & Suffolk Yacht Club, a small marina, well protected in a side basin right next to the fairway with an impressive clubhouse including a restaurant and sanitary facilities. Unfortunately, I don’t meet anyone else at this time of day and so don’t get to enjoy these amenities. The actual harbour seems to be mainly used by feeder boats, with neither fishermen nor freighters to be seen.

Lowestoft – Den Helder, ca. 125 nm, ca. 20 h

The next morning we set off at around 0700 a.m., I don’t have to pay attention to the tidal current on the course to Den Helder as it comes from the side. I put the 2nd reef in the main quite quickly, the wind picks up well into the 6 Beaufort and brings me along quickly. The first half of the route is uncomplicated, but from the early afternoon onwards I have to wind my way between traffic separation areas, deep-water routes and wildlife parks, fortunately always driven by a strong half or rough wind. On the Dutch side, the shipping traffic is considerably heavier, as two shipping lanes converge here. The wind eases very slowly, but is still enough to push the ship to the entrance of the Schulpengat to Den Helder. The last few miles are then motored against the outgoing water. Around 0300 in the morning I moor at the Royal Marine Yacht Club.

Den Helder is the naval base of the Netherlands and you can see young people training on all kinds of ships and vehicles everywhere. Large warships and supply ships come and go here and there is a really huge naval and maritime museum with a huge number of ships from all eras and functions outside.

The club-run marina is small but nice, the harbour master very friendly and helpful, the sanitary facilities first class including free use of washing machines and dryers. There is a small, fine restaurant in the clubhouse with very friendly service and simple but good dishes. Unfortunately, I have to take the train back home early the next morning for a week and therefore can’t stroll around and enjoy the place.

Two important paths crossed for me in den Helder: in 1975, at the age of 16, I sailed out onto the North Sea as a boatman on the yacht of friends from our sailing club. Back then, my aim was to sail via Cuxhaven – Kiel Canal – Klintholm – Sund to Anholt in the Kattegat. And today – almost 50 years later – I am here in Den Helder as the skipper of my own yacht on my way back from France and England.

Den Helder – Cuxhaven, ca. 186 nm, ca. 29 h

A week later I return to the boat and plan to start the very next morning at Slack Water and sail the approx. 180 nm to Cuxhaven in approx. 36 hours non-stop. The wind is forecast to be south-westerly at up to 26 knots, with gusts of up to 30 knots, which promises a strenuous but also fast passage. I plan the route so that I can sail up the Elbe to Cuxhaven in the Late morning of the following day as the water rises.

From the south-west facing main fairway off Den Helder, the Marsdiep, there is a narrow fairway to the NW off the south-west side of Texel, the Molengat, which I would like to use, as it would certainly save me 2-3 hours on the route to Cuxhaven. As I have read about variable depths in Reeds, I ask a Dutch sailor in the club pub in the evening whether the passage is possible without any problems with a draught of 2 metres. He confirms this in principle, but talks about possible ground swells that occur in the event of prolonged, strong westerly winds and advises me to ask the harbour master again the next morning, who is always well informed about the situation in Molengat. The next morning, the harbour master recapitulates the weather situation of the previous days and comes to the conclusion that no bottom seas are to be expected. I decide to give it a go, bearing in mind that I can turn back if the worst comes to the worst.

I set off in the late morning. The water is still rising a little and I cross westwards towards Molengat with a reef in the main. The passage is unproblematic, the fairway is well emphasised and the still moderate south-westerly wind is pushing strongly. There are no bottom seas at the northern exit, but the wind is now so strong that I take the precaution of adding a second reef to the main. I make good progress through the water at 6-7 knots, but only at 4-5 knots over ground, because the tidal current will be running against me for the next few hours. The hydrogenerator hums at the stern and keeps the consumer battery at a good level. A good feeling.

I’m already feeling a bit sick to my stomach, seasickness is lurking in the background. I try to keep it at bay with small snacks, warm drinks and short power naps. There is practically no harbour of refuge on the route to Cuxhaven that I could call at with reasonable effort and risk. In an extreme emergency, I could call at Borkum halfway through the night, but with no chance of getting back on the route the next day against the strong south-westerly wind. In addition, the tidal current would run against me at night at around 0300 when entering the Ems estuary, so that I would have to reckon with a wind against current situation at 7 Beaufort. A clear no go.

In the early afternoon, a Polish 15-metre Bavaria comes out of the fairway between Vlieland and Terschelling and runs parallel to me in a north-easterly direction not too far away. Exactly within my guard zone, so I have an annoying constant alarm. I furl the jib in the hope of slowing down a little and gaining some distance, but as the wind picks up, I can only get back to hull speed faster and faster with a double reefed main. The Bavaria zigzags a lot, sometimes with and sometimes without the jib. Finally, late in the evening, I’m stable about 1 nm ahead and can set up the guard zone accordingly so that calm returns. The wind repeatedly exceeds 30 knots and the sea is rough and high at around 3 metres. But with the wind astern, double reefed main and autopilot, it’s quite manageable. I urgently need to sleep to stabilise my stomach and get rid of the annoying feeling of weakness.

Over the course of the night, I manage to take one or two 30-minute naps and my physical fitness stabilises. It rains from time to time and the wind remains stable at 7 Beaufort. At around 0300, a whole series of very fast ships cross my course off the Ems estuary; I assume they are feeders heading for the mainland from the nearby wind farm. Apart from that, there are very few encounters with ships, so I can take a short rest from time to time. I pass the endless row of East Frisian islands and reach the Weser estuary at around 09:00. There is a lot of ship and radio traffic again. My Polish friends also get a call from Elbe Weser Traffic.

There is not much room here in the ITZ, only about 5 nm between the traffic separation scheme and the shallower coastal areas. Under no circumstances should you go below 10 metres water depth in these conditions. At around 1100 a.m., I briefly come across an offshoot of the Nordergründe off the mouth of the Alte Weser, where the bottom rises to less than 10 metres. The wave pattern changes abruptly: the waves are now 4 – 4.5 metres high and become much steeper. It’s only a matter of minutes before the ship is going to flip. I immediately change course by 30 degrees to the north to quickly get back into deeper water, where the sea immediately becomes more moderate again. The Polish yacht behind me runs even further inland and even holds its course on the flat a little longer until they realise the danger and follow my lead and run out of the danger zone.

Around midday I reach Scharhörn Reef, behind which I hope to find shelter from the rough sea and a calmer sail. There is only half a mile of space between the reef and the traffic separation scheme, which is really very tight, especially as a freighter is coming towards me here of all places: just outside the traffic separation scheme and on the “green”, i.e. wrong side of the fairway. The space between the freighter and the fairway buoys is too narrow for a passage because it becomes dangerously shallow very quickly, so I have to pass it on the wrong side (green to green).

I try in vain to reach him on the radio to coordinate the passage. It’s not very exciting, but everything goes well and then I’m already downwind of the Scharhörn reef and the sea slowly calms down.

For the next few hours we sail up the Elbe as the water rises, accompanied by lively shipping traffic. The wind is still so strong that I continue to make good progress with the double-reefed main alone. When I switch off the autopilot in Cuxhaven to take the main down, I realise that the rudder can no longer be moved with the autopilot switched off. Shock: the linear motor seems to be jammed when switched off, just before entering the harbour in the tidal current. Fortunately, at least there are no rough seas here. I disconnect the drive piston from the quadrant and can steer the boat by hand again without any problems. Woah, that went well again.

Around 0300 in the afternoon I moor in the harbour of the Cuxhaven Sailing Association and am glad that I made it. 186 nm in 29 hours at an average speed of 6.5 knots. Despite the mishap with the autopilot, I’m very happy with the boat and the overall technology. The only thing that really annoyed me was the persistent feeling of weakness and nausea on the way. I put it down to the hasty departure yesterday. A day to acclimatise before the start would certainly have been better. But as is so often the case, there was no time for that because the weather forecast for the following days was unfavourable and the schedule was too tight.

Here comes the end of the most beautiful sailing trip of my sailing life so far. It’s now only a stone’s throw to the Baltic Sea to the winter berth. No, I haven’t sailed as far as Spain and Portugal, but only as far as the northern French Bay of Biscay. And the boat isn’t staying in the water somewhere in the south for the winter, I’m back in home waters. On the one hand, it’s really hard for me to let go of the south as a destination, but on the other hand, I’m also happy about the prospect of having the ship within easy reach in winter and being able to carry out all the repairs and improvements that I already have on my list again. And there are so many beautiful destinations that I can sail to from my home waters in the next few years, maybe to the south again, who knows. I won’t run out of dreams.

Reflection:

What I still find difficult on challenging sea voyages is finding the right balance between persistent pursuit of the goal and blind “head through the wall” stubbornness. On the one hand, you have to summon up quite a bit of energy and perseverance to complete a longer trip single-handed under challenging conditions. On the other hand, you can quickly cross the line into blind stubbornness without even realising it. There is then a danger of ignoring risks and overestimating your own resources. When the going gets tough, it is not always easy to constantly readjust your own assessment of the situation without despairing or getting carried away with unrealistic euphoria.

And I always have to remind myself along the way to keep control of small and tiny sources of error and risks. I often notice – out of the corner of my eye, so to speak – that I need to fix something and think: I’ll remember that and do it later. But then there are so many other things to do that I often forget. It’s not uncommon for a small mistake at sea to trigger a chain of consequences that can ultimately lead to disaster. In this respect, I try to stick to the iron rule: everything I see, I do immediately or at least write it down on my to-do list. Even if this sometimes leads to annoying delays, in the end it pays off at sea as good preparation.

And you can’t have enough time. Especially if you don’t want to beat up the ship and the crew, but want to adapt to the weather and sea conditions in order to have as pleasant a passage as possible, you should avoid any external time pressure as far as possible.

2 Responses to From Brittany back to the Baltic

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

This site uses Akismet to reduce spam. Learn how your comment data is processed.

-

Recent Posts

Recent Comments

- Calypsoskipper on Replacing saildrive diaphragm

- Calypsoskipper on Replacing saildrive diaphragm

- Patrik on Replacing saildrive diaphragm

- Christian on Replacing saildrive diaphragm

- Calypsoskipper on Expose Finngulf 39

Kalender

March 2026 M T W T F S S 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 Tags

12 V Verkabelung 12 V wiring Anchor windlass Ankerwinde Biscaya Bora Segel Bretagne Brittany Camaret sur mer circuit distribution Cornwall Cowes Cuxhaven Den Helder Diaphragm English Channel Falkenberg falkenbergs Båtsällskap Falmouth Gezeitensegeln havarie Hydrogenerator Lewmar Ocean Membrane MiniPlex-3USB-N2K Nordsee Norwegen Oxley Parasailor Plymouth Ramsgate Saildrive Saildrive diaphragm Saildrive Membrane SailingGen Seenotrettung Segeln in Tidengewässern Sjöräddnings Sällskapet Skagen Skagerak Stromkreisverteilung tidal navigation tidal water routing Tidennavigation ÄrmelkanalArchiv

Kategorien

Toller Bericht mit viel nützlichen Infos, danke. Da ich eine ähnliche Tour ab Mai 24 vorhabe kann ich die Informationen gut gebrauchen. Mal gucken ob ich es bis Galizien schaffe. Grüße Jochen

Hi Jochen, danke für dein Feedback. Ich wünsche dir einen schönen Törn und kann sowohl die Bretagne als auch die südenglische Küste nur wärmstens empfehlen. Falls du an einem Gedanken und Erfahrungsaustausch interessiert bist, melde dich gerne. Viele Grüße. Alex