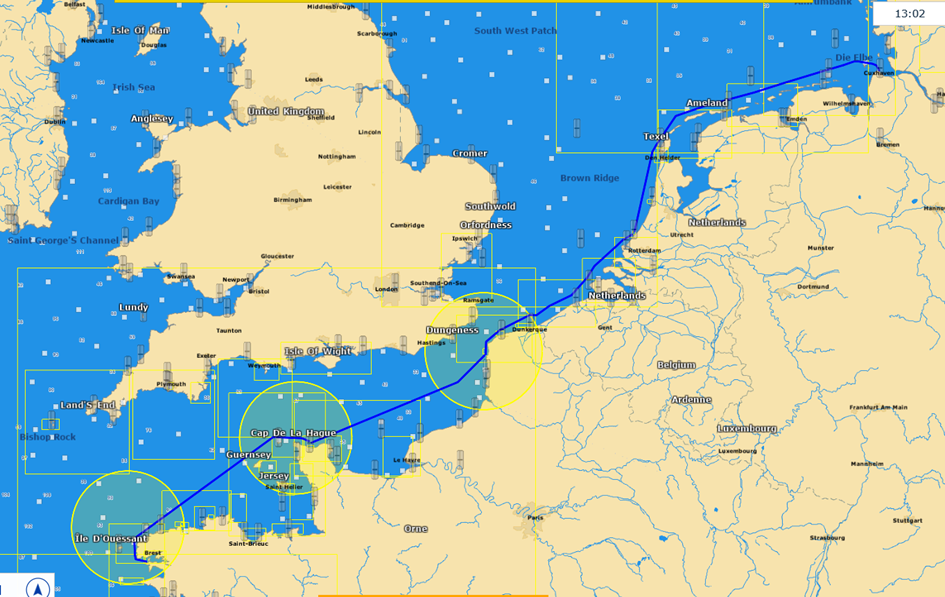

My plan was to sail the ship from the Baltic Sea to northern Spain. As a Baltic sailor, I have a lot of respect for sailing in tidal waters. Accordingly, good preparation is crucial to me.

Here is a video with my general plan.

On the route from Cuxhaven to Brest, there are several passages in the English Channel and on the coasts of Normandy and Brittany where the tidal current – especially at springtime – can easily reach 4 knots or even much more. I don’t want to pass such places when the wind is against the current or in other unfavourable constellations, so I plan these passages accordingly. Specifically: I want to pass Cap Griz-Nez with maximum current, the wildest passages at Cap de la Hague and the Chenal du Four at slack water.

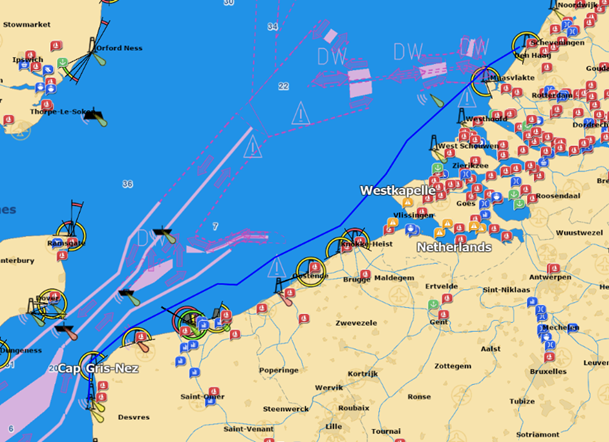

Using the example of Cap Griz-Nez – the narrowest point in the English Channel with a tidal current of up to 4 kn – I would do it in such a way that – coming from Scheveningen – I arrive at Dunkerque with the beginning of the outgoing current and then sail the next 40 nautical miles or so to Boulogne Sur Mer with the water running out, i.e. with the current running with me. In Boulogne, I want to go into the harbour, wait for the water to rise, get some hours of sleep and then sail on with the water running out.

So the question is: when do I have to start from Scheveningen in order to pass Dunkerque in time with the beginning of the outgoing current and then make the passage of the English Channel via Cap Griz-Nez to Boulogne with outgoing currents and as high a speed as possible over the ground before the water begins to rise again.

For me as a simple-minded Baltic sailor, it seems obvious at first that I would have to arrive in Dunkerque shortly before high water and then have a good 6 hours to sail the following approx. 40 miles to Boulogne with outgoing water and then arrive at Boulogne with low water.

However, there are two false assumptions in this consideration.

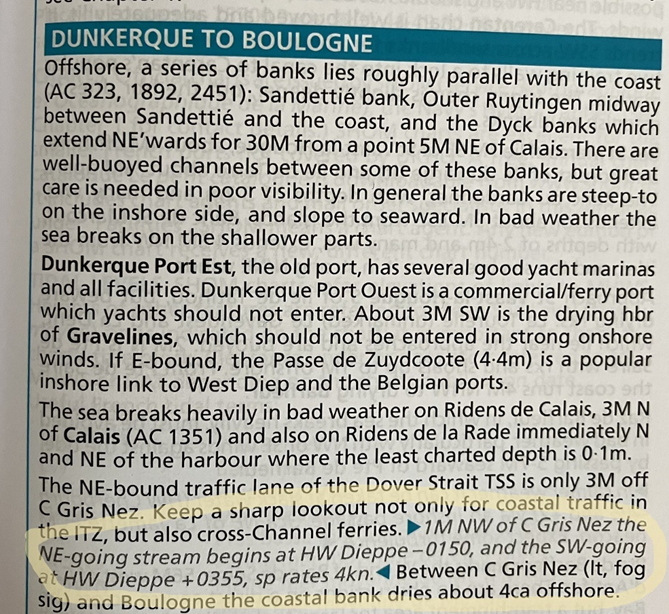

For one thing, the time window for the passage is only a good 5.5 h, due to the time difference in the duration between rising and falling water. In this region, the water regularly rises about half an hour longer, i.e. in the NE direction, than it falls, i.e. in the SW direction. Specifically: SW-setting tidal current between Dunkerque and Boulogne runs only about 5 h 45 m. Ok, this half hour can certainly be neglected.

Much more serious, however, is the considerable time lag between high tide and the onset of the outgoing tidal current (see also Kenterpunktabstand Tidestrom – Lexikon der Geowissenschaften (spektrum.de)). According to the tidal charts of the British Admiralty, the tidal current in the English Channel between Dover and Calais is just under 4 h, i.e. the water only begins to run off again in a SW direction 4 h after high tide. The Reeds writes about the capsize point distance before Cap Griz-Nez, related to HW Dieppe:

The time of high or low tide is therefore irrelevant for the actual route planning (as long as the destination ports are accessible regardless of the tide), the decisive factor is the time of capsize of the tidal current in the passage under consideration.

For example, on 25.10.2022 at 0145 CEST HW is in Calais, but the tidal current capsizes there only at 0530 CEST and then begins to run again in the SW direction.

Also in the waters north of the Channel Islands, the capsize point distance is approx. 4 h. These are extreme peculiarities in these places, which one must know and take into account. In other places, the capsize point distance is usually considerably less, e.g. in Cuxhaven only just under 1.5 h, but still.

Where does one get the current data in the first place? On the one hand, there are the classic sources such as the Atlas of Tidal Currents or Admiralty Tide Tables or their reduced illustrations in the paper nautical charts or in the Reeds Nautical Almanac. Personally, I find these sources inaccurate, risky and time-consuming to use and prefer an electronic nautical chart in which the tidal currents are displayed – precisely localised and related to the planned route and with reference to the time on board.

So how to plan the passage?

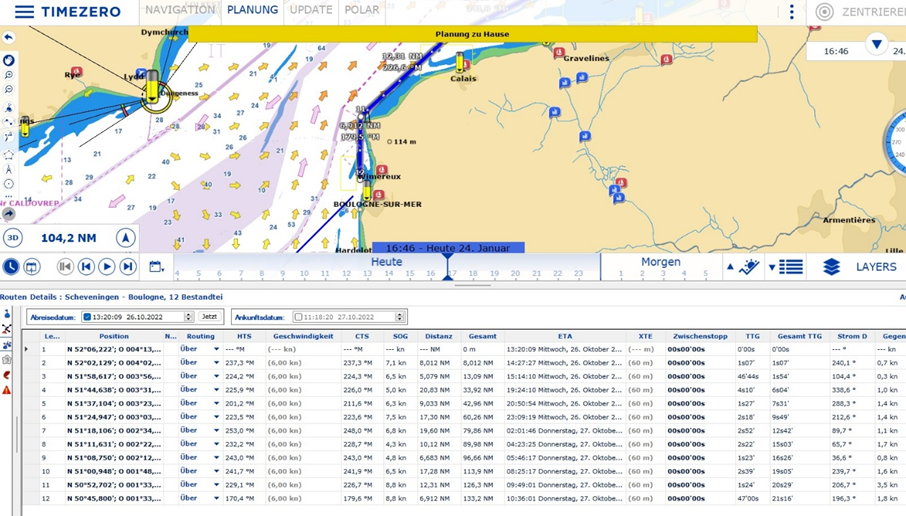

The distance from Scheveningen to Boulogne is just over 130 nm. Spring tide after new moon is on 25.10.2022. I plan to start on 26.10. in the afternoon with planned arrival off Boulogne just before the tidal current capsizes on 27.10. at 11:18.

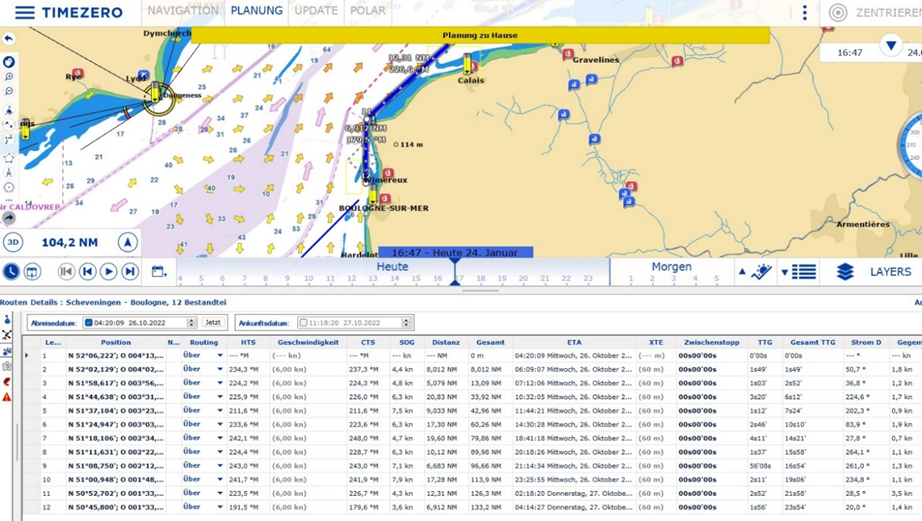

The route planning assistant of the navigation programme “timezero” calculates a journey time of 21 h and 16 m, assuming an average boat speed of 6 knots (STW) and taking into account the tidal current, but not the weather on the route. The passage of Cap Griz-Nez in the section between Dunkerque and Boulogne is calculated with SW setting outgoing water with current speeds of up to 3.5 kn in places: Legs 11 and 12 with average SOG of 8.8 kn.

If you do the countercheck and set the departure time on 26.10.22 to 04:20, the route assistant calculates a journey time of 23 h 54 m, taking into account the tidal current.

Over the entire route, the time difference between the two variants is 02 h and 38 m more. In relation to Legs 10 -12 (approx. 40 nm in the Dunkerque to Boulogne section), the time difference is still 2 h 9 m. On the 12 nm section (Leg 11) between Calais and Cap Griz-Nez, the current runs along at 3.5 knots in the favourable variant, while in the unfavourable variant it runs against at 3.5 knots. I find it impressive how much the variants differ in travel time and it seems sensible to plan carefully here. Anyone who has ever struggled for hours against a current of sometimes more than 3 knots, and possibly in a “wind against current” situation, knows what I mean.

Of course, over a distance of 90 nm and approx. 15 h sailing time, you always have to reckon with not being able to make a spot landing at Dunkerque exactly at the planned time. The assumed average speed of 6 kn (STW) can very quickly prove to be wrong due to adverse or particularly favourable circumstances: if the wind is favourable, the ship will run permanently at 7 – 7.5 kn without any problems. In any case, precise weather routing based on the current forecast is necessary shortly before the start of the passage. Nevertheless, if the arrival time at Dunkerque is so unfavourable due to unplanned circumstances that I have to reckon with mostly counter-current during the passage of Cap Griz-Nez, I would go in shortly after Dunkerque and wait for the tidal current to capsize.

The realisation of the sometimes considerable time gap between HW or NW and the capsizing of the tidal current was already very enlightening for me and I am glad that I was able to take this into account accordingly in my planning.

-

Recent Posts

Recent Comments

- Calypsoskipper on Replacing saildrive diaphragm

- Calypsoskipper on Replacing saildrive diaphragm

- Patrik on Replacing saildrive diaphragm

- Christian on Replacing saildrive diaphragm

- Calypsoskipper on Expose Finngulf 39

Kalender

March 2026 M T W T F S S 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 Tags

12 V Verkabelung 12 V wiring Anchor windlass Ankerwinde Biscaya Bora Segel Bretagne Brittany Camaret sur mer circuit distribution Cornwall Cowes Cuxhaven Den Helder Diaphragm English Channel Falkenberg falkenbergs Båtsällskap Falmouth Gezeitensegeln havarie Hydrogenerator Lewmar Ocean Membrane MiniPlex-3USB-N2K Nordsee Norwegen Oxley Parasailor Plymouth Ramsgate Saildrive Saildrive diaphragm Saildrive Membrane SailingGen Seenotrettung Segeln in Tidengewässern Sjöräddnings Sällskapet Skagen Skagerak Stromkreisverteilung tidal navigation tidal water routing Tidennavigation ÄrmelkanalArchiv

Kategorien